Europeans often draw parallels between modern informal urbanisation in the Global South and the organic development of their cities in pre-modern times. This comparison overlooks the crucial context in which European urbanisation occurred—a context defined not only by the physical construction of cities but also by the concurrent emergence of the nation-state and the concept of citizenship, with its associated rights and obligations.

Urbanisation in Europe was inextricably linked to the evolution of positive rights—rights that require action by the state to be fulfilled, such as access to housing, public services, and social welfare. The very fabric of European cities was woven together with these state obligations, creating a governance framework that supported the needs of urban populations as they expanded (not without struggles).

In contrast, informal urbanisation in the Global South lacks this parallel institutional grounding and civic advancement. While urban growth is dynamic and rapid, it often occurs outside the sphere of state intervention, meaning that residents do not necessarily benefit from the same negative and positive rights as their counterparts outside of informal settlements.

Moreover, informal settlers are often criminalised because their occupation of land is typically framed as illegal. This criminalisation stems from the application of Western-style property regimes and legal codes that prioritise individual property rights over collective rights or the right to housing. As a result, informal settlers are viewed as “trespassers” or “squatters,” even when their settlements are the only viable housing option available to them due to systemic poverty, a lack of affordable formal housing programs, exclusion from credit or exclusion from urban planning processes.

The label of criminality not only strips informal settlers of legitimacy and dignity but also reinforces cycles of marginalisation. Criminalisation becomes a tool for exclusion—justifying evictions, the denial of services, and the lack of political recognition. This creates a precarious existence for informal settlers, who live in constant fear of displacement and are deprived of basic infrastructural investments that could improve their living conditions. The informal settlement, then, becomes an embodiment of both spatial and legal liminality, where residents are physically present but politically invisible.

The absence of a strong regulatory and welfare framework means informal urban settlements frequently lack access to essential public goods and services such as clean water, sanitation, education, and healthcare, making life exceedingly hard for these populations. The lack of state acknowledgement and the criminalisation of their existence prevent informal settlements from being integrated into the wider city, leaving residents cut off from opportunities for socio-economic mobility.

This distinction underscores a fundamental misconception: whereas the informal growth of European cities in past centuries ultimately gave rise to formal rights and state responsibilities, informal urbanisation in the Global South today is largely disconnected from such formal institutional and political advances. Consequently, the organic growth of these cities is marked by a lack of systematic state support and recognition, which reinforces inequalities and undermines the potential for equitable development. The disconnect between informal urbanisation and state frameworks serves to entrench social divisions rather than foster inclusive growth, making it crucial to challenge and reconsider how these urban spaces are understood and governed.

Informal urbanisation is a process deeply enmeshed in the socio-political and economic exclusions that drive spatial inequalities in the Global South. It cannot be understood solely through the lens of spatial morphology or architectural analysis, as is often the European inclination. Instead, the political agency of informal settlers and their actions can be seen as a form of “insurgent citizenship” in reference to James Holston’s ideas that directly challenge formal urban policies and neoliberal models of property.

Informal urbanisation represents a counter-narrative to the formal city. Informal settlements are not just spaces of need but also sites of production—places where urban residents actively construct both their built environment and their collective identities in response to state neglect and exclusion. This “counter-production” can be seen as a form of counter-public in urbanisation, in the sense that it represents a collective space where marginalised voices assert their presence, articulate their needs, and challenge dominant narratives about urban growth and legitimacy. Residents of informal areas develop alternative forms of infrastructure, governance, and social relations, often outside the bounds of formal legal recognition.

Informality is both a spatial and a regulatory phenomenon—a duality that intertwines the physicality of urban space with the legal frameworks that define what is deemed legitimate or illegitimate. Informal urbanisation thus reflects the limits of the state’s capacity or willingness to incorporate certain populations, as well as the limits of a neoliberal urban agenda that prioritises market-driven development over social equity.

In this sense, informal urbanisation is not just a by-product of economic and demographic pressures but a manifestation of a particular kind of political failure: the inability of the state to adapt to the needs of all urban citizens, particularly those who are economically or otherwise marginalised. We need a shift in perspective—from viewing informality as a ‘problem to be solved’ or a ‘model of spontaneous spatial organisation’ to seeing it as an expression of urban agency that formal institutions must acknowledge, respect, and integrate into broader urban policies, while simultaneously recognising the negative and positive rights of informal dwellers, thereby fostering a more inclusive urban development framework that accommodates diverse forms of urban life.

I have explored these ideas in depth in two edited books and an article:

Ballegooijen, J. v., & Rocco, R. (2013). The ideologies of informality: Informal urbanization in the architectural and planning discourses. Third World Quarterly, 34(10), 1794-1810. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.851890

Rocco, R., & Ballegooijen, J. v. (Eds.). (2019). The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization. Routledge. See where to buy the book here

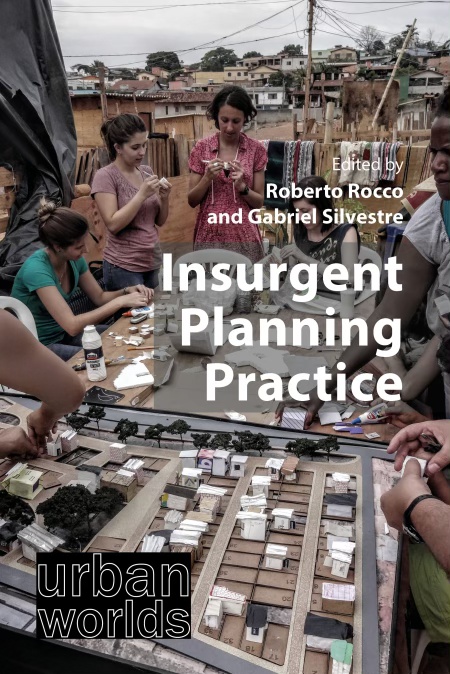

Rocco, R., & Silvestre, G. (2023). Insurgent Planning Practice. Agenda. See where to buy the book here.